Last month, shortly after publishing my two collaboration posts with Sidd Muchhal (one on his Substack and one on mine), I reached the milestone of 100 subscribers. While this was a welcome affirmation that I’m not just shouting into the void, it also reinforced to me that I needed a better name for the blog than “Casey’s Substack,” especially side-by-side with something as unique as Kaloramic. Eventually I settled on what we have here: Meanderings, a word of dubious word-ness but one that reflects what I want to encapsulate in a meta sense.

To give you a sense of what I was going for, the other word that kept popping into my head was jaunt, which is similar to meander in terms of meaning and energy. In its contemporary usage, a jaunt refers to a pleasurable excursion, a short, leisurely journey. Even before I had written my “Welcome” post, I jotted down a description for the Substack page in which I invited you to “Come wander with me!” To this end, my October post about birds in Buenos Aires was inspired by several jaunts during my first month in this beautiful city that has become my new home.

Even so, when considering the blog’s name, I had to be mindful of its — for lack of a better descriptor — vibe. Jaunt has a positive connotation, but (at least, to me) also evokes the words it looks and sounds like, most of which aren’t as friendly and fun: taunt, flaunt, gaunt, vaunt, daunt, haunt.1

A closer look revealed that centuries ago, jaunt used to signify a wearisome trek, and possibly developed in English alongside “daunt,” infusing a sense of discouragement and intimidation into the trip before it had even begun.2 In the sense of essaying forth that I described in my first post, making a sincere attempt at something challenging, this dualism resonated with me — could a jaunt simultaneously be arduous and pleasurable? Perhaps it should!

Of course, jaunt did not win out in the end. I identified a few other Substack pages that are named “The Jaunt” or some derivative thereof. More importantly, if I were to home in on the aspect of my writing journey — and each individual post that it comprises — that I wanted to highlight, it wasn’t necessarily how much effort or exertion it required from start to finish.

This brings us to meander, which as an action does not necessarily imply a finish. To meander is to follow a winding, intricate course, taking many turns, perhaps retracing one’s steps, with or without an eventual destination in mind. Some sources imply that to meander is to wander aimlessly, although this is not intrinsic to meandering in my view. Meandering could begin without a crystal-clear objective, but after looping and curving a bit, stopping to catch your breath or admire the view, you might discover a purpose along the way.

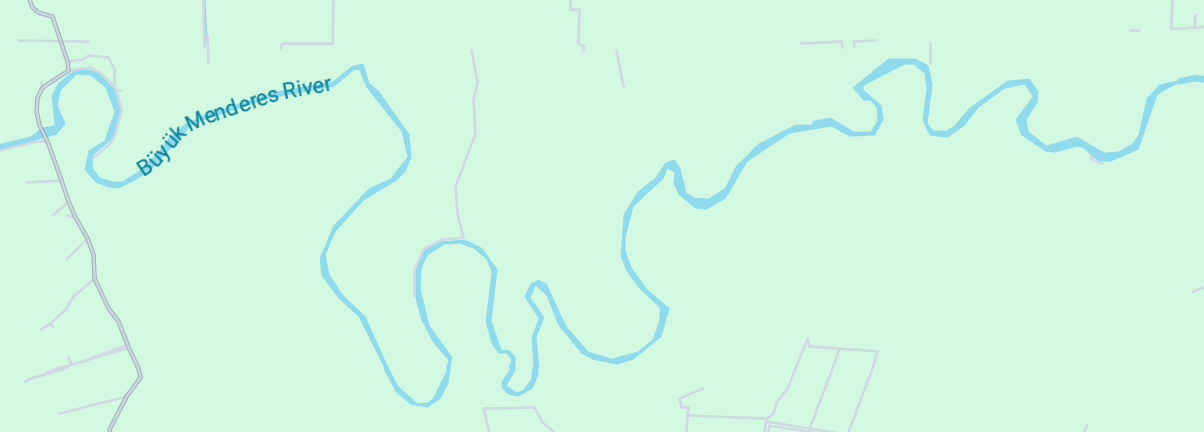

Unlike most English etymologies that trace a word back to Greek or Latin, or all the way to Proto-Indo-European, the word meander stands out for being derived from a name. A river in present-day Turkey now known as the Büyük Menderes was once called Μαίανδρος, or Maeander. Maeander, one of the many sons of Oceanus and Tethys, was also the god of that river, although I was unable to ascertain whether he was named after the river or vice versa.

According to Strabo’s Geography, the Maeander was famed for its bends and curves: “Here the Maeander becomes a large river… running in a direction excessively tortuous, so that from the course of this river all windings are called Mæanders.” Ovid wrote in Metamorphoses that the river, “winding doubtful,” inspired Daedalus in his design of the labyrinth that imprisoned the Minotaur on the isle of Crete. In this account, it is implied that the river had such an intricate and convoluted course that it doubled up on itself at certain sections: “back and forth it meets itself, until the wandering stream fatigued, impedes its wearied waters' flow.”

As with the archaic connotation of jaunt, these classical references to Maeander stand in contrast to the contemporary image of a casual, languid meandering. The image of a labyrinth evokes desperation, taking turn after panicked, frenetic turn in order to escape. Even the river’s waters are exhausted after the umpteenth meander, wanting nothing more than to travel in a “gentle and unruffled stream.” I am grateful that as the word evolved in English, it developed a more relaxed, rambling association.3

In Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative, author and creative writing professor Jane Alison writes that a narrative may take an “extravagant arabesque of detours” before reaching its destination: “A meander begins at one point and moves toward a final one, but with digressive loops.” My love of the footnote betrays a tendency toward digression, which I view as enhancing rather than distracting from the narrative. Stories that travel in a straight, uninterrupted line are boring, after all.

One of the books that stuck with me last year, which I drew from in July and October, was How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell. As an artist, Odell is very conscious of form; in her book about resisting the attention economy, she frames a narrative around her observation of birds, roses, and her own attention and attentiveness to her natural surroundings. In this way, the book itself weaves and meanders, imparting tidbits of wisdom throughout but defying strict categorization as a self-help book or an art book or a manifesto or anything else.

Similarly, the book The Mushroom at the End of the World that I referenced in October takes the form of a series of excursions to collect matsutake mushrooms. Although the book is quite technical and social science-y, it is also multisensory and evocative. Its prologue is entitled “Autumn Aroma” and its interludes between sections include “Smelling” and “Dancing.” It relies just as much on feudal Japanese poetry and present-day harvesters’ insights as it does on theory and scholarship. And in terms of its form and shape, the multispecies assemblages that I discussed in October take center stage; in one example, “matsutake stories draw us into pine stories and nematode stories,” woven together with humans and capitalism.

It is certainly possible that, to a completely new reader, Meanderings doesn’t completely answer a question that I’ve received several times even in the last few days: “So, what do you write about?” I think it does, however, make a statement about what I write, or how I write.

It is for this reason that I use the gerund form rather than simply “meander” or “meanders.” If a meander is a bend in the river, meandering is rowing steadily, navigating those turns, choosing when to paddle furiously or take a breather. Meanderings is therefore to be understood as a collection of journeys, accounts of essaying forth, some more jaunty or jaunt-y than others.

I wrote earlier that while meandering, you could discover a purpose along the way. The purpose could also just be the meandering itself. I concluded my first post in July with some bullet points on what to expect in future pieces, some of which I’ve accomplished and some of which I have not (yet). Even my last two publications were very different from one another, which I did not necessarily plan or anticipate; neither was more or less of a meandering than the other, and both are part of this writing adventure that I have earnestly enjoyed sharing.

So, to the meanderers and meanderthals who have joined me thus far — thank you! I hope you’ll come wander with me some more.

This isn’t a hard and fast rule, of course. I love my aunt. And while haunting is an activity most frequently carried out by ghosts or bad memories, a haunt is also a favorite hangout spot, especially in the sense of someplace you used to frequent in times past, an “old haunt.” According to Wiktionary, my trusty companion on this ramble, the root of “haunt” comes from Old English and French words for reside, inhabit, and returning home. Its spooky connotation probably comes from Shakespeare, and now we have haunted houses frequented by ghosts and spirits even though, in a hyperliteral sense, all homes are haunted.

The Wiktionary page for jaunt also posits that the vibe shift from the late 1500s to jaunt’s contemporary usage was likely influenced by the word “jaunty,” meaning swaggering and cheerily self-confident. I was shocked to learn that jaunt and jaunty share zero etymological origins; jaunty is more closely related to genteel and gentle, somehow. I know that I’m not the only one who thought that jaunty and jaunt were leaves on the same branch, though. You can imagine a jaunty, ostentatious traveler from the 1700s returning from a strenuous, days-long journey to wide-eyed peers, boasting (vaunting, even) “Oh, that? A mere jaunt!” to see how we arrived here.

I recently discovered a related word that is primarily used in Britain (if it is really presently used at all), “maunder,” which means to babble or speak in a disorganized or indistinct way. A maunderer is therefore one who mumbles or speaks indirectly, either in terms of what they’re saying or how they’re saying it. Even though maunder has been primarily used to refer to speech, it can also be used as a synonym for meander. Whether this comes from its similarity to “meander” or its similarity to “wander,” or neither, or both, we’ll never know for certain.

But this gets straight to the point and says there.

Love this - a much more thoughtful reasoning for a Substack name than Kaloramic!