the promise of violence

fear, justice, and what we condone

![Goya - The 3rd of May 1808 in Madrid - [1814] | The painting… | Flickr Goya - The 3rd of May 1808 in Madrid - [1814] | The painting… | Flickr](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!bJ92!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F35448893-d153-45ac-9acb-783dabdaa470_1024x787.jpeg)

My heart had been steadily sinking, and it managed to find its way to the pit of my stomach by the time we made our way through the reinforced glass doors to the lanes. The feeling started during the safety demonstration, where our safety officer ran through an explanation of the guns we’d be firing. We had planned this outing to The Range in Austin well in advance of a group trip to visit one of our friends at the beginning of December. I had been saying to my family that I was afraid of how much I might enjoy the shooting range. I hadn’t anticipated this full-body sensation, though, heart racing, trembling like an old shopping cart being pushed too fast.

Our instructor, whom we’ll call Kenny, was a diminutive older gentleman with twinkling eyes and a twang. We had arrived a bit late due to traffic, and he told us that we’d get through the safety presentation quickly so we could maximize our time shooting. That didn’t stop him from sharing stories about his relationship with guns; his time as an armorer in the Air Force; Top Gun: Maverick and 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi; the time someone peered down the barrel of a live, loaded gun in the lane we were about to enter.1

The safety presentation itself was short and efficient, really more of a demonstration of Kenny’s facility with each of the four guns, which ranged from a pistol to an AK-47. It was simple — after all, according to Kenny, eight-year-old kids in Africa were using AK-47s. If we hadn’t asked follow-up questions, his time showing us how to use the guns properly may have made up 10% of our time in the classroom.

Being the coastal elite that I am, I had never touched a real gun before that day. I wasn’t the only one of my friends who was feeling uneasy going in; three of us said we might just watch. Eventually we got over the trepidation. We each tried shooting all four guns, trying each one several times, went from jumping at the BANG of the AR-15, loud even through the ear protection, to firing it ourselves and feeling the BANG in our shoulders, absorbing and assimilating the force into our bodies.

Young people in America carry violence, or the threat of violence, in our bodies. As much as we use ironic humor to deflect from how it feels, it’s impossible not to internalize the active shooter drills, the reminder every few months that it could have been us, our campus, our concert, our church.

On the first day of school in upstate New York ten years ago, we had an active shooter drill, only it wasn’t clear whether it was a drill, since it was the first day of junior year of high school, and an intentional drill on that day was improbable. We learned later that someone had discovered “BB gun paraphernalia” in a bathroom trash can. I remember feeling a sense of blankness adjacent to dread, but if the dread were in a different place, located outside of my body but still looming. I think if I actively let myself give into that fear, I would have irreparably lost some part of my soul by now. So I keep that dread away and chuckle with my high school friends and tell myself that it can’t happen here.

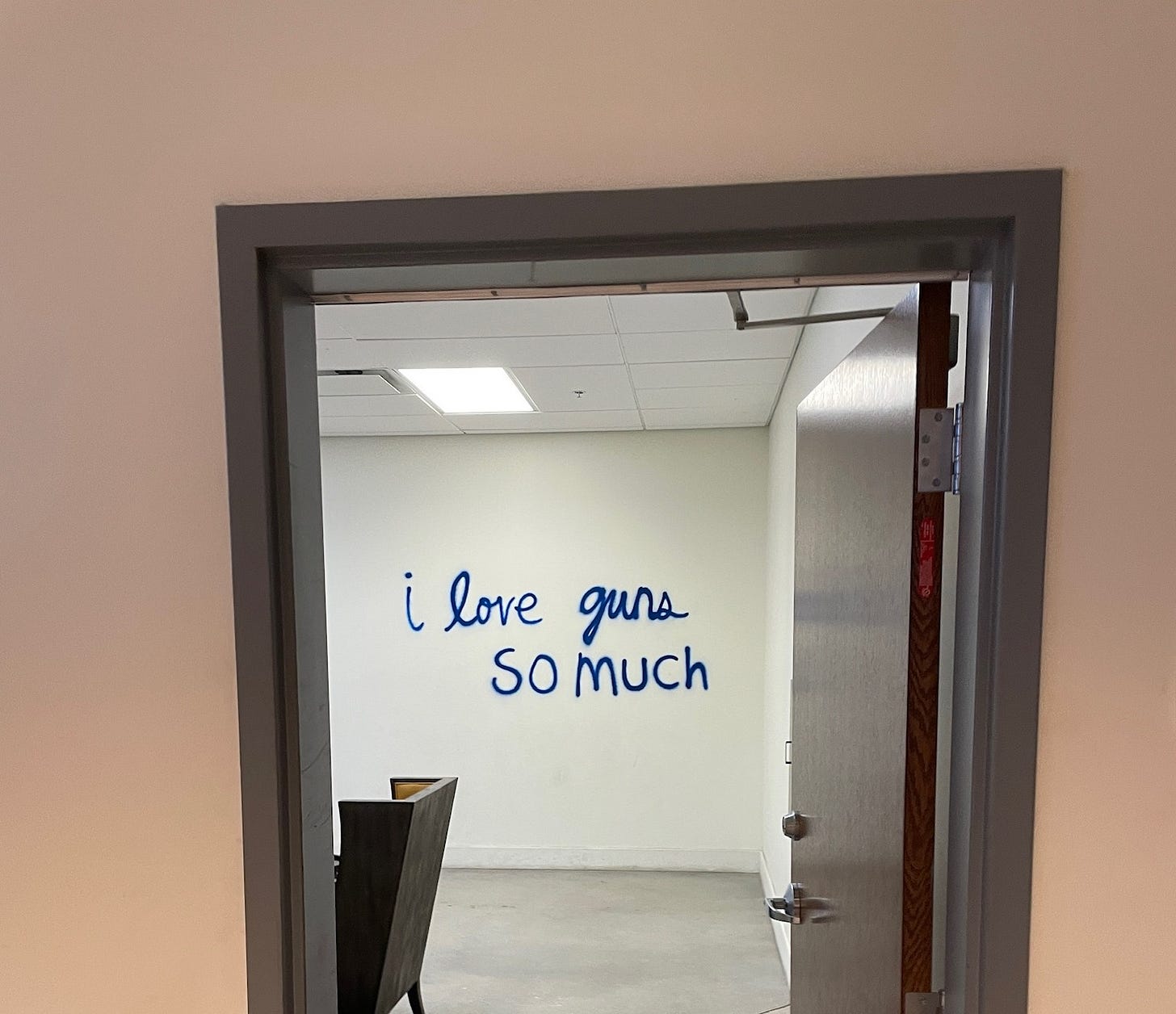

What creeps me the fuck out about guns and gun culture in America is how eager people are about using lethal violence against other people. It isn’t just a respect and love for the intricate, beautiful machinery of a firearm, as Kenny might have asserted. It’s the signs in front yards declaring that trespassers will be shot, the “shoot first, ask questions later” mentality, that these people have a gun and they’re not afraid to use it.2 Shouldn’t they be? Shouldn’t someone with so much respect for such a destructive tool be in awe of its power, should understand better than anyone else that it isn’t something that should be at all taken lightly?

Maybe it’s gone out of a vogue a bit, but I remember when a mainstream argument on preventing school shootings was arming teachers, as if they don’t already have enough to worry about, and in general expanding open carry to act as a deterrent against mass shootings. As if enough guns in the public sphere at all times would create a sort of herd immunity against the gun violence that plagues no other country but ours. It’s so incongruous to me that a considerable percentage of the population would prefer a heavily armed society, where the expectation upon stepping out in public at any given time is that there will be people open-carrying, or concealed-carrying, literally ready to kill.

It raises the question of what kind of violence we accept, and against whom. Presumably the people who welcome the idea of more guns in public have a general idea of who they’d like to see armed, members of an ingroup who share a common conception of justice: against whom violence would be justified, and under what circumstances. Perhaps against people who could be imagined to have different conceptions of justice, or who simply don’t belong in the imagination of an ideal society for whatever reason.

It was quite a month for vigilante justice. It seems that, by addressing the subject, I am obligated to release a disclaimer, a “click accept to continue,” stating that I do not condone violence and I do not encourage vigilantism. Discussions of Israel’s genocide in Gaza over the last year have been similarly policed by those who refuse to engage without receiving a vigorous condemnation of Hamas from the other side. Who are we, individuals in a broken society, to condone and condemn?3 Who am I to denounce the killing of Brian Thompson, whose company denies more coverage than most other major health insurance company, and against whom the resentment of hundreds of thousands of Americans has been so clearly felt since Luigi Mangione shot him in the street in New York City?

It isn’t just that, though. It isn’t just that I am but one person whose condemnation holds no power, to whom the premise of the demand to “denounce” this act of violence is total bullshit. It’s that I’m a young American who holds the threat and the promise of violence in my body and my spirit. This makes the expectation to take this individual act of eliticide seriously — and to consider jokes about Thompson’s application for sympathy being denied, or the memes about Mangione and the fact that he is hot, in bad taste — laughable.

And this quote from Welcome to Hell World, one of my favorite newsletters, sums up some things nicely:

I know I repeat myself on this all the time but the idea that one death is a tragedy while the more routine bureaucratic violence carried out against millions of people every single day for profit is just how things go is so grossly offensive to me.

…But no, I do not celebrate this man's death. I simply mourn for all the millions of others who have been made to die — been killed in fact — by companies like [Thompson’s]. People whose white collar killers are often never even blamed never mind held accountable.

The situation is especially absurd in light of the hypocrisy that would be mind-boggling if it weren’t so commonplace. In May, then-24-year-old ex-Marine Daniel Penny put a man named Jordan Neely in a chokehold on the subway in New York, killing him. The most generous interpretation of the incident would allow us to accept that Neely was behaving in such a way that made people on the subway fear for their safety, and Penny took action to prevent him from harming anyone. This interpretation does not explain why he held the chokehold for a minute after Neely’s body went limp, after someone in the subway car had exclaimed “You’re gonna kill him!”

It’s indisputable that Penny killed Neely. Last month, a grand jury acquitted Penny of negligent homicide after the charge of manslaughter was dismissed when the jury deadlocked. What we have to reckon with is what we do with that verdict, whether we consider it justice, whether that act of violence is acceptable. Penny has disappeared from the new cycle, just as Mangione has (although he’s big on RedNote), but he will likely maintain his status as Favorite Boy of an American Right obsessed with performing masculinity and violence. Move over, Kyle Rittenhouse.

One of the most impactful articles I read in 2024 was “The Invisible Man,” a firsthand account of what homelessness in America is really like, published in Esquire in November. Its author, Patrick Fealey, used to write for established publications like the Boston Globe and Reuters before health issues drove him to homelessness. In the essay, he describes routine encounters with policemen and passers-by alike, the majority of which are characterized by suspicion and, often, disgust. He describes being chased out of parking lots, along with the refrain: “I have every right to be here.”

Fealey writes:

Many of you could be where we are—on the street—but for some simple and not uncommon twist of fate. This is part of your rejection, this fear that it could be you. You deny that reality because it is too horrific to contemplate, therefore you must deny us. And the moneyed reject us because they know they create us, that we are a consequence of their impulse to accumulate more than they need, rooted in a fear of life and the death that comes with it. Nothing good comes of fear, only destruction, and America has become a society of fear, much of that fear cultivated to divide and control.

There’s a special kind of contempt that is reserved for homeless people in the United States. Politicians often perceive them as a problem to be solved, or at least kept out of public view, since more often than not their constituents see them as a threat to their safety or property value. It isn’t as if there is zero truth to this perception; in New York, where at any given moment you might be accosted, sometimes aggressively, by someone experiencing homelessness, the generally understood rule is to not make eye contact and go about your business. Much less often do we consider the cumulative impact on a person of being ignored by the vast majority of other people surrounding them, and how that callous disregard might lead them to exhibit the type of loud, attention-seeking behavior that frightens people, independent of any intent to enact violence.

Can you imagine how it might feel to not only be going through mental and/or physical health issues, but also struggling every day, and often failing, to obtain even your most basic physiological needs, all the while other people do everything they can to pretend you aren’t there and to ignore your pleas for help? I can’t, and I won’t pretend to.

People experiencing homelessness are undoubtedly subjects of the despicable fantasies of those who seek excuses to enact violence on other people, fantasies that Penny was able to make reality. He claims that he would not have been able to live with himself had the man he killed been free to inflict harm upon anyone else. What kind of violence do we accept, condone, justify? As another one of my favorite newsletter writers, A.R. Moxon, described in his discussion of these murders last month:

Maybe Neely even was a danger; unhoused people tend to be desperate, after all, and desperation can make people unsafe. But I also remember that we live in a world where millions of people are systemically abandoned to suffer and die on the streets even though housing them would be cheaper, and I note that it is not the people suffering homelessness who decided to make society work that way, so we might wonder if it was Jordan Neely creating the danger, or if it was someone else making a choice somewhere else.

One of the most appalling manifestations of how homeless people are seen and treated as less-than-human is the encampment sweep, whereby local governments contract backhoes and bulldozers to forcibly relocate people living in tents, destroying their property in the process. A ProPublica project from last month visualized the consequences of these sweeps, which often come with very little warning and without consultation of those impacted. People lost birth certificates and Social Security cards, prescriptions and medications, musical instruments and journals, clothes and sleeping bags. Effectively, among the only belongings of some of the most vulnerable citizens are unceremoniously crushed up and thrown away, along with their dignity and trust in those who claim to be helping them.4 I’ve seen it happen in D.C. — it’s heartbreaking.

I cannot begin to comprehend how such routine violence against one’s personhood may begin to impact one’s conception of self. This banal callousness, policy decisions made from air-conditioned chambers that upend the lives of vulnerable people while manufacturing consent and deflecting ire toward those very people, is one of the primary reasons I want to be a journalist and a storyteller. But before that, I work toward being a more compassionate member of my community wherever and however I can.

I may hold violence in my body, bearing witness to it and internalizing it, yet I still believe we can move past fear to reach something resembling understanding and empathy.

Shooting a gun for the first time made me feel fragile, like I could shatter at the lightest touch, or that the wind might sweep me up into a thundercloud. It was raining when we left, and I was hollow and cold. But I had felt a nervous exhilaration as well, which sent grins across my face like distant flashes of lightning illuminating a dark room. I was with some of my closest friends, and we could comfort one another, cheer each other on, and feed off each other’s energy.5

I don’t know if I’m ever going to go back to a shooting range, and I doubt I’ll ever develop a comfort with guns. I’m glad I did it, though. It gave me a lot to think about, and since our day at The Range was during the interim period between when Thompson was killed and Mangione was arrested, my personal experience with those guns will always be entangled with that bizarre moment in time.

One of my primary resolutions this year is to let go of fear. I am not generally an anxious person, but I have found that I harbor a great deal of fear in my body that paralyzes me even when what I want more than anything is to act. Thinking about violence and writing about it meant that I had to confront some of this fear and try to unpack it without giving into my tendency to compartmentalize. This is part of why it took so long for me to work through this essay. Reflecting about lethal weapons and the capacity to kill necessarily meant that I had to gaze into the abyss of the “fear of life and the death that comes with it” that Fealey described.

In this case, I’m going to reject my instinct to sheepishly apologize for publishing a piece about old news. If anything, it is a step toward honoring my resolution to myself, especially since much of my fear still centers around writing and publishing. Sharing, vulnerability, insecurity, and all that. On the other side of the coin, however, we saw the swearing in of a fascist yesterday, flanked by his favorite oligarchs, and his first slew of executive orders was characterized by institutional, bureaucratized violence against marginalized people in America. This discussion doesn’t end when news cycles end. How we protect vulnerable people from violence, and how we approach these painful reckonings about violence and justice, will be defining questions of any resistance worth its salt.

As always, thank you so much for reading! I do not plan on letting as much time elapse between posts as I did between this one and my last. If I can establish a monthly cadence for 2025, I’ll be happy. Depending on how things are going, I may even go for twice a month. I don’t expect to be able to release my fear overnight, but it helps to have a community of friends, writers and readers alike, to keep me going, so I really am grateful if you’ve made it this far. <3

I’d like to assume that this story ended without incident, but Kenny never concluded the anecdote.

In my last piece, I wrote about how we need each other. One of the most pervasive issues keeping us from one another, as I described, was what I referred to as social atomization: it’s easier (and tacitly encouraged) to consume hyper-personalized content fed to us by algorithms and predatory social media platforms than to make connections with other human beings in social settings. Although I am primarily referring to a fundamentally 21st-century phenomenon, I think it has its natural precedent in the atomization of the nuclear family in American culture. There are certainly exceptions, and I’m also generalizing what could be a whole essay unto itself, but to a large extent the consolidation of the suburban family comes at the expense of deeper community ties, third spaces, etc. Even while my friends and I were in Spain, we noticed and talked about how there were clearly more elderly people out and about, often hand in hand with someone much younger, whereas in the United States elderly folks are pushed out of society and isolated more and more. This is something I had already noticed from living in Argentina for over a year.

This atomization, combined with rising general mistrust of institutions and other people, gives us the “no trespassers” signs, the presumption of suspicion, that other people are potential adversaries until proven otherwise. Imagine if we could healthily assume good faith of our neighbors! Imagine if individualism were seen as weird and antisocial rather than the norm!

https://x.com/InternetHippo/status/1718107575781404897

This experience is unfortunately not unique to homeless people. The inaction of successive US (and global) administrations to take climate change seriously has led to some of the most expensive and destructive natural disasters in recent history to become routine and commonplace. Last month’s hurricanes and the fires in Los Angeles earlier this month demonstrated that parts of the country that were considered “safe” can no longer be considered that way. Yet as more and more Americans find themselves threatened by the potential of losing everything, real estate and insurance companies are doing whatever they can to protect their bottom lines, which has recently meant (respectively) lobbying to expand development in high-risk areas and drastically inflating the costs of home insurance, or refusing to renew/provide plans altogether. I wrote about these phenomena in Jacobin a few days ago.

After the shooting range, we went and got some of the best barbecue I’ve ever had, which also helped.

"trembling like an old shopping cart being pushed too fast".. nice one, Casey!

Great read and so much truth. Violence really is engrained in us—even if we’re not the ones realizing it, the reality of it is always lingering.

I woke up panicked to the sound of a gunshot the other night. Then I remembered I’m not in the US anymore, and the calm returned to me once I realized it was just thunder.

I dated a guy in/out of high school whose family was super into guns. They took me to a range to shoot for the first time when I was 18. I went with him, his mom, dad and his two younger siblings. It was definitely not an intuitive experience for me.

Fast forward some years to find out his little brother was imprisoned for murdering his wife. Guess how he did it?

It was both the most shocking and simultaneously unsurprising news I’ve ever received.

Violence feels seldom surprising these days.