"bending and aligning reality"

on trust | el salvador | and promises of golden ages

donald trump’s “golden age”

The Twitter/X bio of the White House reads: “The Golden Age of America Begins Right Now,” quoting from Trump’s inaugural address. This caught my eye when I clicked on one of its characteristically cruel tweets from last month, where it followed that depraved Studio Ghibli AI art trend to depict an ICE officer deporting a crying woman.

ICE recently deported 238 Venezuelan migrants, merely suspected of being gang members solely based on their immigration status and their tattoos, to one of the world’s most brutal mega-prisons, located in El Salvador. Liberal cries for due process fall upon deaf ears, as Republicans don’t care about the Constitution or treating people with dignity, as long as they get credit for deporting people. It doesn’t matter whether they be a gay asylum-seeker with a rainbow autism awareness tattoo or, for speech allegedly deleterious to American foreign policy, a postdoctoral fellow at my alma mater’s Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding. For Trump and the GOP, the cruelty is the point, and the more horrific the punishment that these innocent people receive, the happier they are to relish in that suffering and indignity.

The “golden age” that Trump evokes does not include everyone, not even all Americans. To rephrase: the White House intends to bring about a golden age for some Americans at the expense of other Americans, or dare I say most Americans. That there is no metric by which to define a golden age is part of the point, too. Like with the word “woke,” the tactic is to invent a term and then use it as a benchmark, a sort of adjustable target, pursuant to a broader strategy of transforming the realm of acceptable discourse and legitimizing despicable, unconstitutional policies.1 It’s all worth it because the golden age of America “has just begun,” or begins right now, or is beginning right now, or will begin after it gets a bit worse now, or a lot worse now.

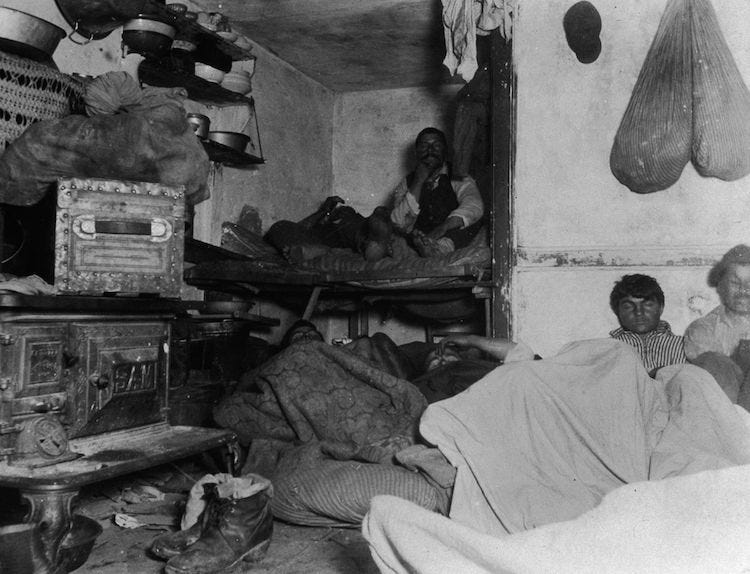

Trump’s model, however, draws from a particular “golden age” in American history.2 For a long time, he has expressed nostalgia for the Gilded Age — a period in which wealth inequality was at its peak and businessmen speculated wildly and flaunted their riches grotesquely. That sounds an awful lot like the 2020s, doesn’t it? Some might argue that we’re already in the second Gilded Age, and we have been for at least a decade. There’s still more to go for Trump to really bring it home, though, and the last few months are a testament to that.

The name of the Gilded Age came from a satire of the promised “golden age” following the Civil War and Reconstruction, with Mark Twain and his co-author Charles Dudley Warner noting that despite those promises, all they were seeing was a gilded veneer that failed to completely obscure the serious social and economic issues of the 1870s. Reconstruction ended in 1877; exactly a century later, Jimmy Carter took office and began to dismantle the regulatory state, work that Reagan continued with gusto, ushering in a new era of unchecked corporate malfeasance and drastic inequality.3 The combination of an increasingly lenient regulatory environment and cultural acceptance and glorification of wealth accumulation contributed to two interrelated crises — Black Monday (1987) and the more prolonged savings and loan crisis — resulting from the perverse interplay of speculation, fraud, and greed.4

Between Black Friday (1869) and Black Thursday (1929), wealth inequality ballooned. There also were a disconcerting amount of financial panics with different naming conventions. Speculative bubbles swelled and popped, fomenting the Panics of 1873, 1884, 1890, 1893, 1896, 1901, 1907, and 1910. Small shareholders suffered, and while there were certainly titans who toppled in many of these cases, the burden of each of the panics and recessions of this time period fell upon the working people whose life savings were mere toys for bankers to play with.

“life was a game, and the chips were dollars!”

I’ve recently been immersing myself in literature from and/or about this time period to better understand what we’re living through today. Most recently, I finished The Moneychangers (1908), a little-known book that the prolific muckraker and socialist politician Upton Sinclair published two years after his magnum opus, The Jungle. It is a loosely fictionalized account of the events leading to the Panic of 1907.

The Panic of 1907 was set in motion by a failed attempt to corner the market on stock in a copper company, which had a ripple effect causing the failure of banks holding that stock as collateral; at the same time, a prominent brokerage firm had borrowed heavily using the stock of a steel and railroad company as collateral, a stock whose price was rapidly declining, in the hopes of a payoff from the copper scheme. A certain John Pierpont (J.P.) Morgan stepped in to save the day amid the chaos, holding court for bank presidents and the Treasury Secretary to avert a total disaster. Part of the solution involved the consolidation of U.S. Steel, Andrew Carnegie’s powerful monopoly that Morgan originally helped form, with the aforementioned steel and railroad company — an acquisition that Teddy Roosevelt would not have stood for amid the antitrust fervor of the Progressive Era, if not for the stock market being on the brink of total collapse. The transaction went through, confidence surged, and the final crisis was averted. Morgan, of course, made out fabulously well by lending all this money to save the banks at high interest rates, not to mention his interests in the resulting steel monopoly.

Trust companies were all the rage at the time, essentially serving as investment banks that held and managed people’s assets as trustees, with fewer legal obligations to back their holdings than actual banks.5 Part of what made the Panic of 1907 such a fiasco was the failure of the Knickerbocker Trust Company — at the time, New York’s third-largest trust companies — due to the involvement of its president, Charles Barney, in the copper scheme. When depositors began to pull their holdings, Morgan refused to allow his bank to serve as a clearing house for Knickerbocker, and it went under. Stocks plummeted and, because so few holdings at the time were secured by actual money, several other banks and trust companies failed.

The protagonist of The Moneychangers, Montague, is a corporate lawyer who is recruited to lead the purchase and renovation of a railroad company linked to a steel trust; he naively accepts the role, but when he learns that the bidding processes will not be fair and that the new directors intend to inflate prices for their own benefit, he withdraws himself from consideration, disgusted. Still connected to that world, though, Montague joins forces with a journalist to follow the saga. They soon discover that the financiers essentially engineered the crisis on a whim.

At first, Montague struggles to believe that this could happen.6 What Montague learns at the end of the story, however, is that Dan Waterman (clearly modeled after J.P. Morgan) set up the entire railroad and steel company arrangement, encouraging Stanley Ryder (Barney) to purchase it and lend out money backed by the steel company’s stock, and then intentionally smashing the stock’s value, abusing Ryder’s trust and completely ruining him.7

Sinclair’s genius is injecting human will and caprice into the story of the financial panic. Early in the novel, Montague introduces his friend Lucy Dupree to high society after she moves to New York, and she becomes an object of interest for both Ryder and Waterman.8 She ends up falling for Ryder and rejects Waterman’s advances — in fact, Waterman tries to assault her, but Montague rescues her. Waterman vows that he will have his way no matter what, but Dupree fades into the background as the railroad/steel scheme dominates the plot. When the pieces fall together at the end, Montague realizes with horror that Waterman carried out his revenge, ruining the economy and defrauding millions of Americans in the process. Ryder, like Barney in 1907, commits suicide at the novel’s end, as does Dupree.

This part of the story is fully fictional, but what matters is not whether or not it happened that way, but that it could have. This plotline also draws from an understanding of what drives these people: power. Over dinner, Montague hears one of Waterman’s allies (and someone he had thought of as a friend) make an offhand comment that he doesn’t care about money. In that moment, he comes to a central realization: “Life was a game, and the chips were dollars! What he had played for was power!”

A century later, Donald Trump, or his ghostwriter, wrote in The Art of the Deal:

Money was never a big motivation for me, except as a way to keep score. The real excitement is playing the game.

Depressingly, Montague’s journalist friend tries to publish the bombshell story of Waterman’s secret meeting with the other financiers before the stock market opened the following day, but the owner of the newspaper, who was in the pocket of those elites, cut it. What they ended up publishing — and what ended up being a dominant narrative in the months following the Panic of 1907, when Morgan was heralded as a hero — was a case study in revisionism.9 The same phenomenon takes place nowadays, with mainstream media outlets largely accepting and regurgitating (and thereby reinforcing) the underlying premises that justify exploitation and corruption instead of interrogating them and exposing for being the societal cancer that they are.

“bending and aligning reality”

Before starting The Moneychangers, I finished Trust (2022) by Hernán Díaz, a Borgesian metafictional novel told over four fictional “books”: (1) a novel-within-a-novel (Bonds) about a powerful banker and his wife; (2) the unfinished autobiography of the banker on whom that novel is based; (3) the memoir of the ghostwriter and former assistant of that banker; and (4) the banker’s wife’s journal (Futures) that the ghostwriter discovers 60 years after her death. It’s a bit disorienting at times, but I loved it. The allegory is not quite as direct as Sinclair’s — Andrew Bevel, the fictional banker, does not necessarily stand in for any single historical figure.10 In fact, Díaz takes the conclusions of The Moneychangers one step further. Instead of theorizing about a cabal of elites who end up averting a catastrophe, Díaz invents one godlike figure who brought about global financial ruin simply because he could.

The impetus for Bevel to write an autobiography with the help of Ida Partenza, his ghostwriter and narrator of the third book, is the perceived libel of Bonds, which portrays Bevel as the architect of the Great Depression. To be clear, in the “real life” of Trust, this was accurate: Bevel bought gold and liquidated all his stocks in the months before Black Thursday. However, the central figure to the narrative is Mildred, Bevel’s wife, whose analogous character in Bonds suffers from a degenerative mental disease that compels Bevel to subject her to a convulsive therapy, which ends up killing her. According to what he tells Partenza, Bevel takes the most issue with his portrayal of Mildred as a sick, insane person rather than the “simple creature” that he loved, and he implores Partenza to center her in his autobiography and emphasize “Her delicate nature. Her frailty. Her kindness.”

The second book of Trust, the autobiography, is never published. Central to Bevel’s narrative is this lesson that he allegedly learned from his grandfather, also a financier: “that self-interest, if properly directed, need not be divorced from the common good, as all the transactions he conducted throughout his life eloquently show.” Bevel also describes himself as a polymath, responsible for inventing statistical analysis and probabilistic patterns that gave him unique insight into how the market was destined for failure in 1929, something no one else seemed to realize. The reader learns by the end of Trust that the truth, both about Mildred and about Bevel’s own prowess (and commitment to the common good), is more complicated — but I won’t spoil it!

Bevel tells Partenza early on in the novel something more central to understanding him — and the type of person that he represents — than is clear at that point in the novel:

My job is about being right. Always. If I’m ever wrong, I must make use of all my means and resources to bend and align reality according to my mistake so that it ceases to be a mistake.

He provides an example of this principle later. After Bonds, written by the fictional author Harold Vanner, is published, Bevel takes decisive action to bend and align reality such that it never existed. He binds Vanner to an indefinite contract, buys a controlling stake in its publishing house to keep Bonds in print forever and buys every copy and pulps them, all while overwhelming Vanner with lawsuits that he doesn’t care about winning. He stiffens at Partenza’s suggestion that this was excessive. “How incongruous would it be to find traces of Vanner in a world where Vanner never existed?” he replies.11

Bevel, like the financier at whom Montague marvels for his lack of scruples, does not appear to care about money or any display of ostentatious wealth. Of course, it serves as an essential tool to allow him to bend and align reality. But Bevel has no interest in high society, with all its mansions and yachts, which was central to the elite lifestyle during the Gilded Age, and consequently to the plot of The Moneychangers and other books of the time period. The power in and of itself to shape narratives — and, in doing so, create new futures by rewriting the past — is what Bevel finds so irresistible, which makes for a surreal reading experience. It’s also the most terrifying takeaway from all of these stories, but especially Trust, with its interlocking narratives and matryoshka books-within-books: can we ever really know that the truth is true, or that reality is real? Or must we simply trust that it is?

trust in the 21st century

In 2012, Trump served as a talking head for the History Channel program “The Men Who Built America,” a whitewashed portrait of the most powerful businessmen in American history, focusing on the robber barons of the Gilded Age, whom he clearly admired. One clip from this series has been making the rounds recently, in which he commented that he likes to buy when the economy is doing badly.

Trump has managed to cultivate a reputation, especially among liberals of the Cheeto/Drumpf ilk, of making haphazard policy decisions because he is a blustering, blundering moron — and while this may hold some truth, the blueprint he follows is that of the men who profited enormously during the country’s worst financial crises. J.P. Morgan used to hold those meetings privately, though. Trump, on the other hand, gestured to Charles R. Schwab in a room full of cameras and praised him for having made $2.5 billion off of the wild market swings that Trump set into motion by abusing his public office and the public trust.12 We are supposed to believe that his “buy” tip on Truth Social, mere hours before the 90-day pause on tariffs was announced and stocks soared, was not obvious market manipulation. His strategy is to put this out in the open, to normalize the massive upward distribution of wealth and the blatant illegality of so much of what he’s done, learning from the mistakes of the robber barons who fell victim to the Progressive Era.

When Trump refers to the golden age of U.S. history, he often invokes the specific time period between 1870 and 1913, remarking that it was the “richest our country ever was.” In 1913, the 16th Amendment re-established a federal income tax in the United States after 40 years, and the Revenue Act of 1913 substantially lowered the tariffs that Trump credits with making us so rich. Equally important to this story, though, is the Pujo Committee, a Congressional committee that was tasked with investigating the money trust, or the alleged Wall Street cabal of financiers that controlled the financial system, suspicion of which surged when the dust of the Panic of 1907 settled. Its findings, including famous testimony from Morgan himself, fostered public support for the above legislation as well as the Clayton Antitrust Act. Amid the information saturation of the digital age, it is hard to know whether a similar committee would have the same impact today. Even so, the success of the Fighting Oligarchy tour demonstrates that there is a popular appetite for this anti-billionaire sentiment.

To a man like Trump, the takedown of the money trust with the establishment of the Federal Reserve (also in 1913), and the general surge in mistrust of elites at the time, is a profound lesson. By bringing the oligarchs to the forefront of his political machine, he ensures that he is always one step ahead of the public narrative, and the establishment media is ill equipped to keep up. Of course, he is aided by a series of interrelated values and movements that have seeped into the public consciousness over decades, including Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth, free enterprise, and the entrepreneurial work ethic, not to mention the very American tradition of not trusting other people. Fictitious mythologies of growth and progress underpin American capitalism, revising history to lead us to believe that the string of years following “Panic of,” as well as the financial bubbles and recessions since the 1980s, are blips and anomalies rather than inherent features of the system.

It’s not just Trump, of course. Elon Musk is perhaps the most despicable outgrowth of the convergence of these hideous facets of contemporary American society. It isn’t just that he is superlatively evil, vindictive, and unscrupulous. Most remarkable to me is that he managed to solidify his position within the American consciousness as someone worthy of respect and reverence simply because of his wealth, rather than any meaningful achievements and in spite of the slew of disastrous actions over his career that he had to retcon later.13 This is a man who was ousted from PayPal for his incompetence and who is only a “co-founder” of Tesla because he entered a pointless, expensive legal battle to make sure of it. Bending and aligning reality.

Over the last several weeks, Marco Rubio and the rest of Trump’s goons have repeated the strategic lies that the Venezuelan migrants they deported, and the international students whose visas they revoked, are terrorists.14 In the case of Kilmar Ábrego García, the US legal resident who was sent to this horrifying prison due to an administrative error, the Trump administration has asserted that he is a member of MS-13 based on hearsay in a 2019 immigration case and has stood by their decision to deport him. When asked about Ábrego García’s case, Nayib Bukele, the president of El Salvador, laughed that he wouldn’t “smuggle a terrorist” into the United States and stated that the question is “preposterous.”15 The Supreme Court ordered the Trump administration to facilitate the return of Ábrego García, but in the same press conference, Stephen Miller asserted that the 9-0 ruling was “in our favor.” Bending and aligning reality.

When Trump says that there’s no reason why US citizens shouldn’t be deported, and there’s no reason why alleged “terrorists” deserve due process, we are supposed to trust that they wouldn’t come after any one of us for the flimsiest of pretenses, send us to El Salvador without due process, and then claim that they have no jurisdiction to effectuate our return home. That is the reality in which we live now.

The Moneychangers ends with Montague declaring that he is going into politics “to try to teach the people.” After his disheartening experiences with corporate law and journalism, he saw no alternative. Indeed, so many of these institutions, from legacy media to the Supreme Court, are rotten from the inside, corrupted by the profit incentive and beholden to the modern-day robber barons. In this way, Sinclair infused elements of his own biography into his character — Sinclair studied law at Columbia but pursued writing instead, and was active in politics as a Socialist and a Democrat for several decades. Throughout his career, he exemplified principled opposition to what he believed to be our society’s most profound ills. In this vein, Montague’s ending monologue resonated with me deeply:

I'm afraid of the grip of this world upon me. I have followed the careers of so many men, one after another. They come into it, and it lays hold of them, and before they know it, they become corrupt. What I have seen here in the Metropolis has filled me with dismay, almost with terror. Every fibre of me cries out against it; and I mean to fight it—to fight it all my life. And so I do not care to make terms with it socially. When I have seen a man doing what I believe to be a dreadful wrong, I cannot go to his home, and shake his hand, and smile, and exchange the commonplaces of life with him.

The Democratic Party has utterly failed to rise to the occasion and confront oligarchs and fascists. Democrats are all too willing to smile and shake their hands. As Sinclair wrote decades after The Moneychangers, reflecting on his failed California gubernatorial bid: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” Even so, I find glimmers of hope in the Fighting Oligarchy tour; in Senator Van Hollen’s trip to El Salvador to speak with Ábrego García and draw attention to his plight; in David Hogg’s Leaders We Deserve project to unseat comfortable, complacent incumbents.

This is Trump’s golden age, not for anyone who believes in dignity for all people. Every day brings a new whirlwind of horrors. I don’t blame anyone who feels overwhelmed. It only requires a bit of attention, though — that commodity under siege by tech billionaires — to notice how powerful people bend and align reality to serve their perverse interests. We cannot trust anything that comes out of the mouth of Rubio, Miller, or any of Trump’s coterie of crooks. We should, however, trust our own discernment, and we should trust one another, we who are ready to fight for justice and equality, if we are ever going to emerge from this dark moment.

Thank you so much for reading! I know this one was long. This is probably the most meaningful piece I’ve written, since it brings together several focal points for me. I want to conclude with some places to follow and support that are doing essential work to report on the encroachment of fascism and oligarchy upon our democracy.

Local journalism is dying. The Groundtruth Project is an organization that supports young journalists in underserved communities, primarily through service programs like Report for America. The American Journalism Project makes grants to local news organizations and partners with communities to launch new ventures in places that have been deprived of local newspapers, and which therefore lack transparency and accountability.

These are some fantastic independent investigative outlets that deserve your support more than ever, including: The Lever; The Nation; Mother Jones; Drop Site News; ProPublica.

To protect vulnerable people in your community against ICE, stay informed about your rights and the rights of undocumented people. The Immigrant Legal Resource Center has compiled resources, as has the Immigrant Defense Project.

In the case of “woke,” the adjustable target is a target not in the sense of a goal, but more like a target at a shooting range, a tautological straw man that can serve as any culture war adversary they want it to be.

President Trump changed the name of Denali, the highest mountain in the United States, back to Mount McKinley to honor his favorite president, the “tariff king,” whose presidency (1897-1901) marked the peak of the Gilded Age and its transition to the Progressive Era. McKinley benefited greatly from the patronage of the so-called robber barons, such as John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan, in exchange for high tariffs and other policies that benefited banking and industrial elites.

The Gilded Age ended around the turn of the century with the advent of the Progressive Era, which saw a range of reform efforts as a response to the corruption, monopoly, and urban poverty of the preceding decades. Progressive reformers expanded voting rights, tackled political machines and corrupt networks, and passed antitrust legislation. In contrast to the 1890s, however, the Democrats of the 1990s and beyond had no interest in challenging the premises of Reaganomics, instead doubling down on neoliberal, free market policies that only further cemented wealth inequality and impunity for corporate malfeasance. That no bank executives were punished after the 2008 financial crisis was, in my view, the nail in the coffin.

There are many complex causes of these recessions, of course. A significant factor that I highlighted in my review of Triumph of the Yuppies last year was the spike in corporate mergers that inflated stock value without really contributing anything of value to the economy, as well as private equity firms stripping existing companies for parts, all in service of increasing stockholder gains. Needless to say, this trend was prevalent during the Gilded Age, and is also a key characteristic of the contemporary economy. Recession incoming!

The distinction between trust companies and corporate trusts at the time is confusing, especially given that the antitrust movement that characterized the Progressive Era primarily targeted the corporate trusts that had, by that point, transitioned to using holding companies instead. The name antitrust stuck because of public revulsion of those trust companies that held monopolistic control across major industries during the Gilded Age, so antitrust law is more accurately anti-competition or anti-monopoly. Trust companies and trust funds, of course, still exist and sort of epitomize generational wealth and wealth inequality in a cultural sense.

“To Montague the idea that there were men in the country sufficiently powerful to wreck its business, and sufficiently unscrupulous to use their power—the idea seemed to him sensational and absurd.”

The public-facing narrative that Waterman presents to his friends is also significant given the antitrust efforts that largely targeted Morgan and his fellow plutocrats at the time; it also has recognizable echoes in the victimization narrative of corporate elites in contemporary America dating back to the 1970s: “‘This country needs a lesson,’ he cried. ‘There’s been too much abuse of responsible men, and there’s been too much wild talk in high places. If the people get a little taste of hard times, they’ll have something else to think about besides abusing those who have made the prosperity of the country; and it seems to me, gentlemen, that we have it in our power to put an end to this campaign of radicalism.’”

Dupree’s naïveté is evident from the beginning of the novel: “‘A speculator!’ exclaimed Lucy. ‘Why, I thought he was the president of a bank!’”

“It was very interesting to Montague to read these newspapers and see the picture of events which they presented to the public. They all told what they could not avoid telling—that is, the events which were public matters; but they never by any chance gave a hint of the reasons for the happenings—you would have supposed that all these upheavals in the banking world were so many thunderbolts which had fallen from the heavens above. And each day they gave more of their spaces to insisting that the previous day’s misfortunes were the last—that by no chance could there be any more thunderbolts to fall.”

I found The Moneychangers after reading Trust because I wanted to read The Jungle, and both were free on my Nook. While writing this essay, it occurred to me that Díaz was likely influenced by Sinclair, and I discovered this interview in which he names The Moneychangers among his influences. In Díaz’s story, Bevel makes his fortune by making opportunistic stock purchases during the Panic of 1907 and declines J.P. Morgan’s invitation to the secret meetings that, in Sinclair’s telling, orchestrated the panic itself. In this way, Bevel exercises a degree of independence, or transcendence, of the money trust. At times, this seems fantastical and unrealistic — which is part of the point.

Partenza later tries to find Vanner in the catalog at the New York Public Library to revisit his portrayal of Mildred in his novel, and is astonished to find that they have nothing at all about him, despite his early success as a novelist and Bonds having been widely reviewed upon publication. “Bevel, one of the Library’s main donors, had bent and aligned reality.”

Schwab’s granddaughter, Samantha Schwab, is deputy chief of staff at the Department of Treasury despite having very little meaningful experience. In a healthy democracy, this nepotism and political patronage would be a massive red flag at best.

As the linked article (from 2009!) concludes: “After all, if all it took was putting money into a company, everyone in the U.S. could consider themselves founders of Tesla, since the government has backed hundreds of millions of dollars in loans the company, like other tottering automotive enterprises, has received.” This ended up being incredibly prescient, since Musk’s current ventures also rely on the same model. Now the American people are bankrolling Musk’s entire net worth, since the president has sponsored Tesla in his official capacity and Musk has essentially been granted an insider position in the government’s contracting mechanisms.

In the case of university students protesting Israel’s genocide of the Palestinian people, the State Department is following a playbook authored by the Heritage Foundation, the same extremist ideology laundering firm that wrote Project 2025, called Project Esther. The strategy of conflating and altogether equating anti-Zionism, or any critique of the Israeli government, with antisemitism aligns with the priorities of conservative Christians and right-wing leaders. It specifically calls for pro-Palestine protesters to be maligned as part of a “Hamas Support Network,” which of course does not exist, but figures into the State Department’s defamation of those they have abducted off the streets without proper cause or due process. Project Esther received no input from Jewish groups and itself peddles antisemitic conspiracy theories. This is no surprise, since the mainstream Republican Party has fully incorporated those conspiracy theories into its brand and identity — naturally, Project Esther does not focus on combating right-wing antisemitism. On April 15, the Jewish Council of Public Affairs and a coalition of mainstream religious organizations condemned the weaponization of antisemitism to justify the erosion of democratic institutions and the infringement on civil liberties characterizing the Trump administration’s policy.

If you want a masterclass from one of the world’s slimiest people on how to bend and align reality, click the Youtube link on “laughed” and listen to Stephen Miller. It’s infuriating, so make yourself a cup of tea in advance.

nicely done casey!

adding “coterie of crooks” to my list of trivia team names