am i capable of falling in love?

craving intensity of feeling, and talking about love on valentine's day

[hello! this is the most vulnerable thing i’ve ever written, but it’s something i’ve wanted to share for a while now. also, i’ve included some tracks from one of my favorite albums for background listening while you read <3 enjoy!]

I told a couple of friends over coffee that one of my New Years’ resolutions was to get my heart broken. They looked at me blankly in response. I backtracked. It isn’t exactly that, but more what it represents: getting my heart broken would mean that I was capable of surrendering to someone — developing a wild, fiery crush, overthinking, obsessing over someone — such that I might yield to them the power to wholly fuck me up. In other words, I’m hoping to prove to myself that I’m capable of falling in love.

I’ve been thinking about love a lot recently. Last year, I declared to my therapist that I crave “intensity of feeling,” of which love is the most obvious example. We went back to that phrase often, at his insistence. I had started seeing this therapist a little under a year ago, around the same time as I realized that I would hesitate when people would ask me how I was doing, which didn’t even always mean that I wasn’t doing well, but that sometimes I didn’t really know how I was doing, which is arguably worse.

This longing for some intensity of feeling didn’t come up during our first sessions. I just didn’t feel like I was feeling any strong feelings (something I wrote in my journal in April), and it was making me unsure of how susceptible I was to those feelings in a general sense. As I wrote in October, I spent most of my life under the impression that I had built walls so fortified that I would be protected from ever missing people, and that loneliness simply wasn’t in my repertoire. I figured out in therapy that this was not the whole truth. Even so, I had certainly put up some walls, some from my childhood and some from when I got my heart broken for the first (and only) time.

That I have indeed suffered a very real and very painful heartbreak is the most compelling piece of evidence that I’m capable of the converse, if we accept the premise that being in love is a necessary prerequisite for the kind of heartbreak that I experienced.1 It was my first semester of college and, wide-eyed but feigning self-assurance, I fell into a series of crushes. First was a sweet boy in my orientation group with amber eyes and a gentle smile who told me he was straight while we walked together in the rain under his umbrella. Second was a less-sweet boy who was attractive and dubiously closeted and ended up telling me over Snapchat that he “lost interest.” Third was a complicated, mindfucky entanglement that left me barely intact.

It doesn’t take any complex psychoanalysis to understand how a new set of walls were erected seven years ago — I can flip back through the archives to see where I responded to “I promise I won’t hurt you” with “ok i trust you.” Promises, trust, and, consequentially, my heart, all broken in textbook fashion.2 I don’t harbor resentment toward him anymore. It was a long time ago, we were young, it was confusing, I know I didn’t do everything perfectly either, and besides, he gave me this experience that I can point to as a time I hurt profoundly.3 Even so, could it be that my heart healed, but gnarled and calloused? And what of these new walls, so tall and imposing?

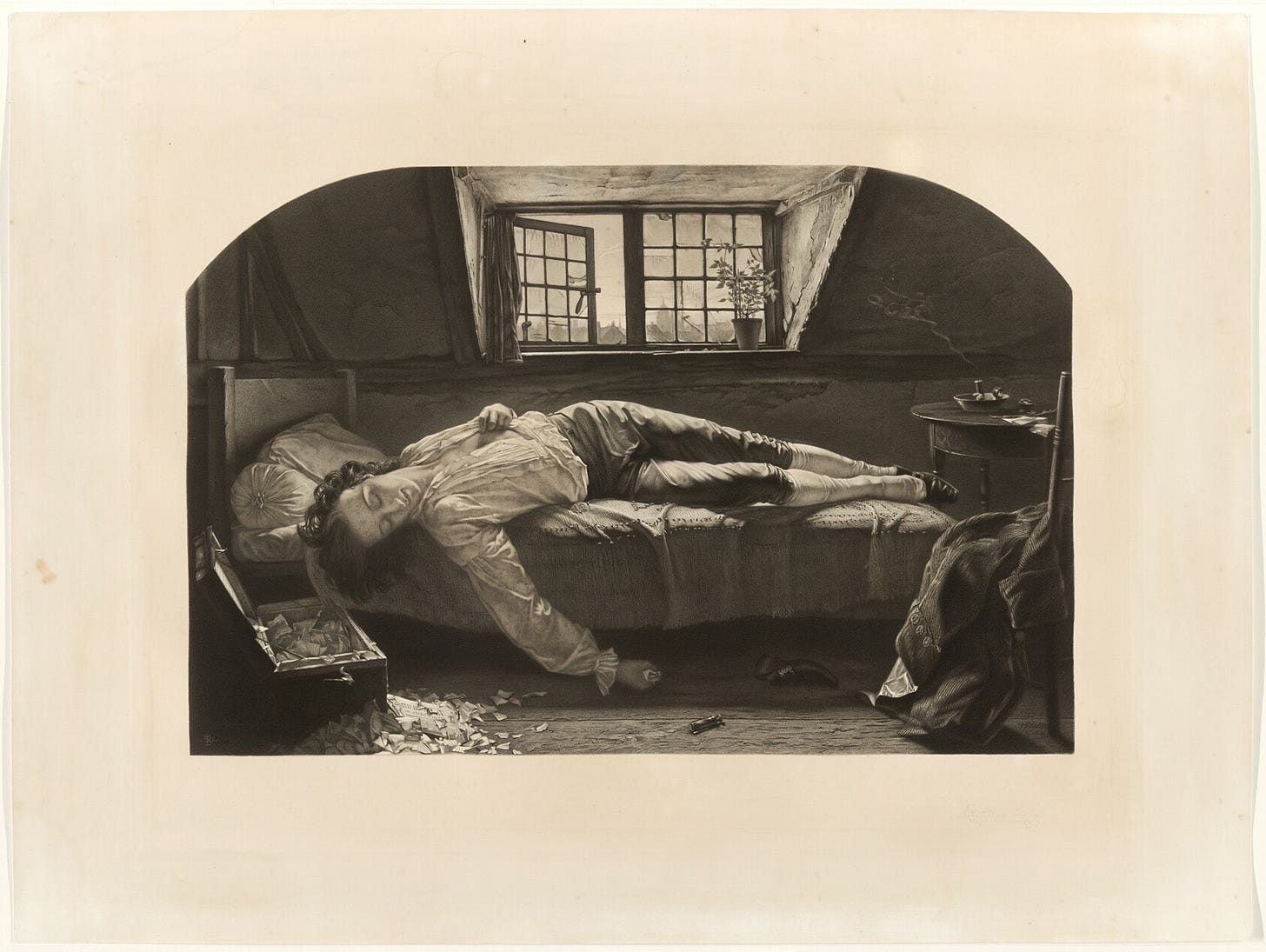

In October, the NYT Modern Love podcast interviewed Andrew Garfield, known for being the most earnest and charming man in the world. Among many lovely things, he says: “The only gateway to true vitality is through a broken heart; acknowledging that our hearts are meant to break and break and break and live by breaking.” Our hearts expand by cracking open. It’s a beautiful sentiment, like kintsugi.4 In the context of the loss of Garfield’s mother, something he is very open about and which causes him to choke up while reading aloud the “Modern Love” essay he chooses, I understand it.5 I can’t help but wonder if what he says holds true in all cases, though. In 2018, I mourned the 18-year-old who could develop three crushes in as many months, dragged underwater by his own too-heavy heart turned to stone, replaced by a new version of myself who could tread water, if just barely.

It felt as if my heart had contracted, not expanded. I took pride in my ability to compartmentalize my emotions, having a few long-term hookups or friends with benefits (or, at risk of being drawn and quartered by the Gen Z police, situationships) at a time, people I could date loosely with no expectations. These arrangements often ended in less-than-ideal circumstances, but I’d get off relatively unscathed, the precipitous distance at which I maintained my heart doing its work to prevent any further scarring. I met many different forms of brokenness over these years, from the man who would only murmur “I like you” into my neck when he was drunk, to the one who said once, bashfully, hiding his face from me, “I like that you’re nice to me,” and sometimes it would look like a mirror and whenever I stopped squeezing my eyes shut I would see the fear.

As I mentioned, I started to work through this desire for intensity of feeling in the middle of 2024. I had just ended my second official relationship, breaking it off for the same reason that I ended my first relationship in high school: I had either fallen out of love or had never fallen in love in the first place. In the context of what I’ve shared above, this was disheartening, but I fought the urge to despair. It provided me with a blank slate; I was starting from square one, but maybe that wasn’t a bad thing. I welcomed this opportunity to step back and assess the situation, to see how years of transformative experiences had truly impacted me and my ability to love, and to tentatively open myself up to new ones.

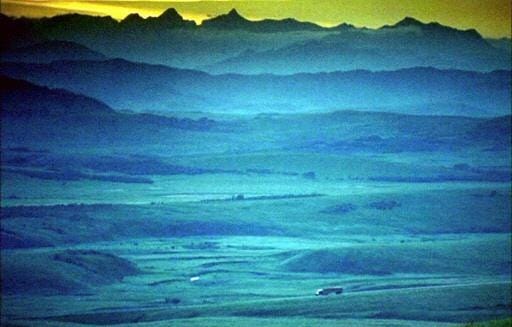

I don’t remember the last time I sobbed as violently as I did on the cold night last August when I watched Brokeback Mountain for the first time in several years. It’s a torturous love story, interspersed with wide shots of the glacial beauty of the Rockies and the sparse, guitar-forward soundtrack by the inimitable Gustavo Santaolalla. It’s a near-perfect film. I went to the short story by Annie Proulx on which it’s based just so I could find the line corresponding to the scene in which Ennis, played by Heath Ledger, collapses to the ground, clutching his chest, as if his heart were literally trying to wrench its way out of his body, after Jack says the iconic line “I wish I knew how to quit you”:

Like vast clouds of steam from thermal springs in winter the years of things unsaid and now unsayable—admissions, declarations, shames, guilts, fears—rose around them. Ennis stood as if heart-shot, face gray and deep-lined, grimacing, eyes screwed shut, fists clenched, legs caving, hit the ground on his knees.

“Jesus,” said Jack. “Ennis?” But before he was out of the truck, trying to guess if it was a heart attack or the overflow of an incendiary rage, Ennis was back on his feet, and somehow, as a coat hanger is straightened to open a locked car and then bent again to its original shape, they torqued things almost to where they had been, for what they’d said was no news. Nothing ended, nothing begun, nothing resolved.

Whatever possessed me to rewatch the film two days later was the same yearning that had occupied my thoughts since my breakup, maybe even during the relationship. Despite the overwhelming tragedy of the story, I couldn’t quiet the voice in my head telling me that I want that, that this love, this intensity of feeling, is something I’m missing. In a way, too, how much I wept was comforting, that such an outpouring of emotion was within grasp, even if it was out of some kind of anticipatory grief for love that I wasn’t sure I’d ever fucking achieve.

My therapist told me that I tend to over-intellectualize my feelings. I responded that it’s because I’m a Capricorn, and he rolled his eyes. It wasn’t just Brokeback Mountain; I’d found in several books that I’d read last year not only vivid, complicated romances but also examples of overwhelming passion, what George Eliot calls “soul-hunger” in Middlemarch, to live one’s purpose furiously. The first essay I posted on Substack was about Zorba the Greek, one of my favorite books and one that is perhaps most deeply rooted in the intensity of emotion that I’m so obsessed with, and I described my ambition to “codify the laws of my own heart” in the shadow of Nikos Kazantzakis and his übermensch protagonist Zorba. It isn’t just romantic love that I fear I cannot access, but some choking paroxysmal ardor, so abstract, yet I hope fervently that to come into contact with it might allow me to conquer the uncertainty that hinders me in so many ways.

Part of my tendency to intellectualize my emotions carries over into my reading. I love to read, of course, but perhaps part of what I unconsciously perform is a cerebral exercise — I highlight quotes furiously, nodding to myself when I feel that I’ve recognized something significant, reveling in imaginary feats of understanding. The perverse effect of this pursuit of gratification is a filter between me and what I’m consuming, avoidance of what might be a more difficult confrontation with the fundamental questions at the books’ core.6 It’s a habit that I’m working on recognizing in the moment and overcoming as I read and consume media. Perhaps because I’m less “familiar” with film, or because the medium is more sensorily immersive, I was more susceptible to letting it wholly crash over me.

Last month I wrote that I hope to let go of fear this year. I’m learning that this isn’t something I can pursue alone, that because accessing love in its many forms is part of what can cure me of the fear that paralyzes me, I cannot give into the temptation to retreat into myself. I’ve been talking and writing through this fear over the last few months, confronting it head-on in a way that I’d never done before. Instead of approaching my history of intimacy and vulnerability through the terms I had established for myself over the past several years of smug compartmentalization, I’m yielding to a more holistic interpretation of the conversations and encounters with men that have brought me closer to understanding myself fully, even if at the time I was only really willing to interpret them in black-and-white terms, of whether or not I “had feelings.”

In fact, looking back, I felt so many twinges, minor heartaches, pangs of feeling that I could easily ignore because they didn’t fit into the all-consuming schema of my heartbreak, something I didn’t even realize I had let develop into a logical standard against which I held everything, everyone.7

In his Modern Love interview, Garfield said: “I long for love. I want to live courageously… I want to make things that are beautiful.” It’s sadly ironic how my fear of giving into full feeling metamorphosed into a fear that I actually was (or am) incapable of tapping into the love that I need, in turn, according to this dark narrative, in order to make beautiful things. I do long for love! I long for love and I challenge the chasmic fear that distances me from it!

At this point I’ve written several times about how marches and protests in Buenos Aires are some of the most profound and gorgeous displays of love and solidarity that I have ever experienced. Perhaps it makes sense that the anti-fascism march on February 1, held in protest of Javier Milei’s homophobic remarks at Davos several days prior, marked the beginning of a new adventure, one that’s still fresh but exciting nonetheless. In the spirit of earnest oversharing, I met a guy. At first, we lost each other in the throng of thousands of people; ten or fifteen minutes later, by some stroke of luck, we found each other again, and I promised that I’d write to him.

And, well, it’s been four weeks, so I won’t make any broad pronouncements, at risk of jinxing it. What I will say is that, on Valentine’s Day, two days after our second date, midway through the Month of Love, I said to myself, fuck it, I have a free afternoon, I believe in romance, and I’m letting go of fear and hesitation. I’m leaning in. I grabbed some flowers from a street vendor who called me “mi rey” and I invited him to go for a walk in the botanical garden.

At one point he stopped and turned to me and asked me what love means to me, qué significa el amor, holding out his hand to me as if he were holding a microphone, his other hand holding the flowers, and he joked that he was reversing the roles by interviewing me, the journalist, while I sputtered and stumbled. He caught me off guard, but he also had no idea how much I’d been thinking about that question over the last few months.

In my apartment, his eye caught my copy of O Principezinho, my favorite book, which my best friend had bought me as a birthday gift from the oldest bookstore in the world (in Portugal, hence the Portuguese — coincidentally his native tongue). He flipped to a random page. He said it would tell us something, like a tarot reading. He landed on Chapter XXII, in which the little prince meets a railway switchman who sorts passengers onto trains that roar like thunder and are gone in brilliant flashes. The little prince asks the railway switchman why they’re moving so fast; were they not happy where they were? No one is ever content where they are, the railway switchman responds.

As I’ve been thinking over and overthinking love, I keep returning to this phrase from the Small Wire essay “in defense of feeling”: Miriam describes romantic love as “a frightening desire to merge into someone else.” At the same time, I came across the word “suffuse” and its derivatives, first in Women in Love and then in Middlemarch, and the word took on a multisensory quality, as light, warmth, love, could spread through one’s entire being, and is it not the asymptotic end state of romantic love in its purest form to reach total oneness with someone, to melt into them? That’s the response I gave to my Valentine-interviewee: when you love someone you want to melt into them, to know them as you know yourself because they are you.8

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t still have doubts; the central question of this essay still looms large. But I’ve also felt, or begun to feel, or felt traces of the suffusive harmony of holding someone’s hand and delighting in what D.H. Lawrence called “presence, pure presence, not to be thought of, even known.” In my vain efforts to know love, have I kept myself from feeling it? Maybe. Maybe my resolution to experience heartbreak was its own exercise in over-intellectualization, a well-trodden path toward intensity of feeling — but what for? I take a deep breath, I shift in my seat. I may still crave that intense emotion, but that does not mean I cannot appreciate the tiny, delicate manifestations of love that may not break over my soul like a roaring wave, but rather wash over my feet, burying them ever so slightly in the sand, suffusing my being with warmth.

Book quotes that have been on my mind

I mentioned some of the books that have made me think about love so much in the past year, so I thought I’d share some of the extended quotes on which I reflected while writing this piece. Until next time!

“‘Life,’ wrote a friend of mine, ‘is a public performance on the violin, in which you must learn the instrument as you go along.’ I think he puts it well. Man has to pick up the use of his functions as he goes along—especially the function of Love.” Then he burst out excitedly; “That's it; that's what I mean. You love George!” And after his long preamble, the three words burst against Lucy like waves from the open sea.

“But you do,” he went on, not waiting for contradiction. “You love the boy body and soul, plainly, directly, as he loves you, and no other word expresses it. You won't marry the other man for his sake.”

“How dare you!” gasped Lucy, with the roaring of waters in her ears.

—A Room with a View

The last sentence was spoken with an almost solemn cadence, and Will did not know what to say, since it would not be useful for him to embrace her slippers, and tell her that he would die for her: it was clear that she required nothing of the sort; and they were both silent for a moment or two…

—Middlemarch

So she relaxed, and seemed to melt, to flow into him, as if she were some infinitely warm and precious suffusion filling into his veins, like an intoxicant. Her arms were round his neck, he kissed her and held her perfectly suspended, she was all slack and flowing into him, and he was the firm, strong cup that receives the wine of her life.

—Women in Love

And he went across to her, and gathered her like a belonging in his arms. She was so tenderly beautiful, he could not bear to see her, he could only bear to hide her against himself. Now; washed all clean by her tears, she was new and frail like a flower just unfolded, a flower so new, so tender, so made perfect by inner light, that he could not bear to look at her, he must hide her against himself, cover his eyes against her. She had the perfect candour of creation, something translucent and simple, like a radiant, shining flower that moment unfolded in primal blessedness.

—Women in Love

There are certainly examples of heartbreak that result from other kinds of loss or trauma. To be fair, though, all of them are relevant to the kind of intensity of feeling, or uncertainty around the relative strength of my feelings, that I was talking through (and the extent to which they are truly physically and/or emotionally distinct is debatable). During one session, my therapist pressed me to talk about my family. When I broke down while talking about my cousin who passed away four years ago, he unfortunately couldn’t quite hide his delight at the triumph of leading me to confirm that I’ve experienced grief. I know he meant well.

Since we were not in a relationship or anything, and there was no clear moment when it “ended,” I was not totally sure that what I was feeling was heartbreak until I started to relate to song lyrics. Then I could say, ah yes, that’s what’s going on. Songs like “When I See You” by Mokita and “Naked” by James Arthur, which had an almost-terrifying degree of applicability to my situation, helped get me through it.

I just finished the book Trust (2022), by Argentine-American author Hernán Díaz, whose title is a double entendre, since it is centered around the finance industry in New York a century ago (Bonds and Futures are two titles of two of the fictional books that it comprises). In Futures, one character writes in her diary while convalescing in a sanatorium in Switzerland:

“Nothing more private than pain. It can only involve one. But who? Who is ‘I’ in ‘I hurt’? The one who inflicts the pain or the one who suffers it? And does ‘hurt’ refer to the inflicting or the suffering?

For those who don’t know, kintsugi is the Japanese art of repairing broken ceramics by piecing together the shards with lacquer infused with gold powder, symbolizing the beauty inherent to the object’s second life, that its having been broken should not be hidden but celebrated. For those who do know, tell me if it’s reached cliché status yet (I feel like it’s headed there).

The essay that Garfield reads is called “Learning to Measure Time in Love and Loss,” and it is stunning and difficult to summarize. What it captures beautifully is that our time on this Earth is finite, so what really matters? The essay concludes by saying: “There are some things you will never do. It doesn’t matter. There is no rush.”

In other words, I came across this quote in a discussion of characterization in contemporary literature that stopped me dead in my tracks. Katy Waldman wrote in The New Yorker that authors like Sally Rooney tend to exploit what Waldman calls the “reflexivity trap,” in which a layer of self-protective irony results in “protagonists who are to be congratulated for spending enough time contemplating themselves that they can correctly diagnose their own flaws.” GULP. I don’t think it was her intent to read me, but I felt called out regardless. Not that I’m looking for congratulations, but I had gotten so used to performing vulnerability and self-awareness (I don’t shy away from talking about “deep” stuff, reflecting on and sharing my feelings insofar as I’m in touch with them) that I didn’t realize how it was holding me back.

I first encountered Waldman’s piece as a citation in the essay “Controlled,” written by Noor Qasim for The Drift, that uses Annie Ernaux’s raw admission of sexual obsession and troubling desire as a backdrop to discuss the millennial sex novel. Being totally, uncontrollably consumed by desire for another person, and to thereby be in touch with some fundamental humanity, is also one of these phenomena of which I’m envious.

My friend Emma and I exchange long, meandering, luxuriant emails every two or three months. When I told her in July about how I crave intensity of feeling and, also, during my most recent visit to the United States, spent time with someone whom I’ve known for a long time and who will probably always hold a little piece of my heart, she responded: “You and I both enjoy pondering the purpose of life, how to most ethically spend our energies, etc., but isn’t that all for the mental and literary exercise?? If we’re being honest with ourselves, what else is the point but to indulge in such attraction and love?? Intensity of feeling!!??”

My focus on romantic love is not to discount the beauty in platonic love, friendship, companionship. Twice in the last two weeks, two different friends have grazed their fingertips across my back absent-mindedly while we sat next to each other in a group, all talking about life, and I felt love in that physical expression of care and closeness.

Casey, I’m proud of you for baring your heart in public. I hope it doesn’t seem so scary now, after the fact!

Love, emotions, doing right by yourself—this stuff is hard. It might be the most difficult task we have, as humans. I’m not sure I have any advice for you beyond this: in Portuguese, the sun sets each night, but is born again in the morning. It doesn’t have a goal, nor is it subject to some eternal torment: it just rises and sets. Some days it’ll be cloudy and the Earth doesn’t get enough light. Some days it’s too strong and uncomfortable for the people here. But the sun still shows up every day and does the thing it does because that’s what it means to be the sun.

For humans, I think that’s finding connection. We cannot help but seek it. Some days we’re cloudy and morose and feeling unloveable. Other days we’re worried about being too intense and burning the people we wish to care for.

But since we can’t do anything else, we might as well surrender to it. Buy the flowers. Choose to let what happened yesterday, or what might happen tomorrow, not ruin what we wish would happen today.

Keep it up, and great piece :)

i’ve admittedly revisited this quite a few times over the past month and it gets better with every read. i deeply relate to the tendency to intellectualize rather than embody—especially because the two often occur simultaneously for me and take up the same amount of space. the catalyst for the numbness you alluded to, this unconscious promise to self that that “you caught me down once but you will never catch me again”—it seems like the kind of thing that develops not necessarily because you’re afraid of rejection (though this can be a factor), but because you can’t reconcile yourself with the fact that a guarantee of any kind was never attainable.

…hmm i think i just intellectualized your intellectualized essay 😂.